Today in Powder River County the nearest emergency room is 80 miles from Broadus. Quality healthcare in southeastern Montana was even more difficult in the early 1900s. With the benefit of history we hope to put some challenges into perspective, and share their consequences. Click here to read a comprehensive Miles City Medical History, from which many of the following information was sourced.

As the newspaper social columns report, most people in Powder River County would travel to Miles City for medical care. There were obstetric options closer to home, mostly in the form of midwives. See the "Obstetrics on the Prairie" section below for a summary of what options were available to women in the early 1900s.

Historical Medical Treatment Options in Southeastern Montana

The early medical history of the Miles City area is linked to the 1870s-established Fort Keogh, where army doctors provided care for the local population. Troops were withdrawn for the Spanish—American War and the post was gradually deserted. Miles City depended upon Fort Keogh for much of its medical help until after its close.

MILES CITY BEFORE 1900

In Miles City itself, one of the first physicians was Dr. J. Jay Wood, who owned the site of the current Masonic building. The 1881 directory from the Yellowstone Journal listed Miles City's population as 1,500, an increase of 400 from 1879. It listed three doctors: CB Lebscher, (who also ran MC drug), HJ. Lynn (with residence on Pleasant Street between 6th & 7th Streets), & R.D. Redd. Their office was over the W.E. Savage store. At that time Miles City had 42 saloons, 8 hotels, 2 stores (Broadwater—Hubbel & Co. and Savage Wholesalers), a barber shop, a blacksmith shop, 2 newspapers (Yellowstone Journal & The Daily Press), 2 telegraphs, a brewery and Huffman/Barnard Photographers.

In Miles City itself, one of the first physicians was Dr. J. Jay Wood, who owned the site of the current Masonic building. The 1881 directory from the Yellowstone Journal listed Miles City's population as 1,500, an increase of 400 from 1879. It listed three doctors: CB Lebscher, (who also ran MC drug), HJ. Lynn (with residence on Pleasant Street between 6th & 7th Streets), & R.D. Redd. Their office was over the W.E. Savage store. At that time Miles City had 42 saloons, 8 hotels, 2 stores (Broadwater—Hubbel & Co. and Savage Wholesalers), a barber shop, a blacksmith shop, 2 newspapers (Yellowstone Journal & The Daily Press), 2 telegraphs, a brewery and Huffman/Barnard Photographers.

Dr. Redd arrived with General Miles and was supposed to accompany Custer but stayed behind to care for an ill Mrs. Miles. It is rumored that whenever town folk saw a crooked arm or leg, they would often remark "there goes one of Doctor Redd's patients"

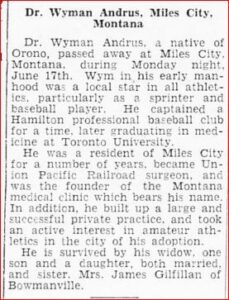

Dr. Lebscher struggled with alcohol and prescribed a whiskey gargle for a sore throat - he left in the early 1900s. Dr. E.B. Fish arrived around 1890, was often drunk, but was a competent doctor if you could find him sober. He left to teach in Milwaukee, selling his practice to Dr. W.W. Andrus in 1893. Dr. Bruning was an early physician known mostly for his sobriety, apparently rare among late 1800 territorial physicians.

Eventually Dr. Andrus organized the clinic of Andrus, Buskirk, Hempstead and Brown. Dr. Garberson and Dr. Randall (ancestor of the Powder River Randalls) later joined them. [operating in the Post Office Building]. This later became known as the Garberson Clinic, which existed independently well into the 2000s.

Dr. Sadie Lindeberg, one of only three women physicians practicing in Montana in the early 1900s. She helped birth more than 8.000 babies in her practice, spanning from 1908 to 1963.

Dr. Sadie Lindeberg, one of only three women physicians practicing in Montana in the early 1900s. She helped birth more than 8.000 babies in her practice, spanning from 1908 to 1963.

Miles City was fortunate to have Dr. Sadie Lindberg practicing from 1908 until 1963. Read more about Sadie Lindeberg in the "Obstetrics on the Prairie" section below. The Montana Women's History Project summarizes Dr. Lindeberg's importance to Eastern Montana:

Dr. Sadie Lindeberg of Miles City had an exceptional career by any standard. She became a doctor in 1907, a time when there were perhaps as few as three women physicians in all of Montana. She practiced well into her eighties and delivered, by her own count, over eight thousand babies in a career that spanned more than half a century. These accomplishments alone make Lindeberg a notable figure in Montana history, but her work helping girls and women through unwanted pregnancies—at a time when pregnancy out of wedlock was shameful and abortion was illegal—makes Dr. Lindeberg’s story truly extraordinary.

MEDICAL TREATMENT OPTIONS IN BROADUS AND POWDER RIVER COUNTY

Closer to the Kingsley area, and the county seat, Broadus steadily expanded its medical treatment options, beginning with Dr. Charles James and Dr. White:

DR. CHARLES H. JAMES - Broadus was fortunate to have two doctors at its inception: Dr. White and Dr. Charles H. James. Dr. White constructed a shed-like home on a riverbank, which eventually washed away, leaving only debris. This location was about a quarter-mile from the Sandall ranch. He departed early in our history with his wife for unknown destinations. Dr. James arrived to homestead in the area, settling on what is now part of the Carl Smith ranch in 1918. He had met Jake George from Coalwood in Miles City, and they planned their move together, each claiming a homestead.

Dr. James became part of Broadus during its early growth, enjoying life as a bachelor. He passed his state examination for a Montana medical license with high marks, showcasing his capability. A graduate of a Washington D.C. medical university, he was a refined gentleman from Virginia. He served during the Spanish American War, and the VFW Post in Broadus is named in his honor. - Mrs. Pearl Nash, Echoing Footsteps

Arguably the most significant event in Powder River County's medical history was the Miller Hospital, rising from the shuttered Cooperative Milling Co. flour mill, purchased by John P. Miller and operated as a flour mill until the drought years in the 1930s. Renovations allowed it to become a rooming house, which then evolved into a hospital - the first patient was a motorcycle victim, Joe Petzsch. Dr. Marvin Amick managed the transition to Miller Hospital, completed during World War II. See the "Obstetrics on the Prairie" section below to learn more about the importance of the hospital to obstetrics in Powder River County.

Miller Rooming House, after flour mill was razed and sold for scraps after the drought years of the 1930s

Miller Rooming House, after flour mill was razed and sold for scraps after the drought years of the 1930s

Across Powder River County, homesteaders tried to solve their own health problems as best they could, before turning to professionals, as documented in Echoing Footsteps:

WALDO R. CAMPER, By Hazel Drane: Most ills were diagnosed at home with the aid of a Dr. book and all the common sense and care that could be mustered. During the winter 1923, one of the twins (Clinton) had become ill. With all the care it was possible to give he continued to worsen. A call was sent out to Dr. Knie who lived on Ranch Creek. Dr. Knie sent word he would come only if someone came for him with a buggy, It was a very cold icy winter. Barefoot horses could not stand up. A team of shod horses and a buggy was borrowed from Ed Hand, a neighbor, and Waldo went for Dr. Knie. Three days later Clinton died, January 31, 1923.